This is the third and final part in my series exploring the events that shaped the electric industry as we know it. If you haven’t already done so, I recommend reading part one and part two first.

As I mentioned in part one, the power industry was born from the inventions and investments of Thomas Edison, along with a handful of visionaries whose careers he influenced. One such man was Samuel Insull.

Humble beginnings to industry titan

Samuel Insull was born in London in 1859. At 19, his modest job as a switchboard operator barely hinted that he’d become one of the wealthiest men of his generation. But, by 23, Insull’s business genius began to show itself. Quick wits and persuasion helped him transform a job opportunity in New York into a role as Thomas Edison’s personal secretary. Once the two men met, their careers became forever linked. Insull quickly rose through the ranks, helping Edison consolidate and organize his sprawling enterprise. In 1892, Edison’s empire was reorganized into Edison General Electric. Despite Insull’s incredible success, he was passed over as president. Frustrated, he relocated to Chicago to assume the presidency of the struggling Chicago Edison Company.

Within a few short years, he turned the company around. One of his most notable improvements was introducing a new pricing model called Time of Use Rates. Rather than a flat fee for electricity, Chicago Edison charged more during busy times and less when demand was low. This encouraged customers to smooth out their usage patterns. This meant the company could build fewer power plants and run existing plants closer to capacity. This simple business model innovation was foundational for Chicago Edison’s amazing turnaround; and it remains the primary pricing model for large electric customers to this day.

GET MONTHLY NEWS & ANALYSIS

Unsubscribe anytime. We will never sell your email or spam you.

Economies of scale and lower prices

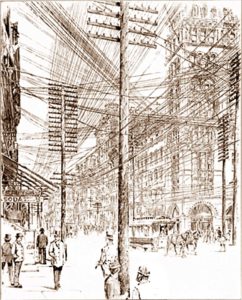

Insull realized that lower prices were the key to attracting more customers. His strategy? Build larger power plants. More infrastructure meant more economies of scale. More scale meant bigger profits and lower prices. Unfortunately, the distribution grid technology invented by his mentor, Thomas Edison, was constraining his ambitions. Direct current (DC) grids could only distribute electricity for a half mile or so. This limited the number of customers that could be reached and kept Insull from realizing the benefit of larger power plants. Worse yet, these small power plants were easy to finance, which enticed entrepreneurs of all kinds to rush into the market. Cities quickly became overrun with competing power companies, all building their own plants and pulling their own power lines. The market was becoming overcrowded and fragmented.

Alternating current (AC) grids changed the game. Suddenly, electricity could be distributed for miles, which vastly increased the number of customers who could be served by a single power plant. This also unleashed the economies of scale that Insull had been seeking. He eventually decided to adopt the competing AC technology.

The race to dominate Chicago’s electricity market was on. Over the next few decades, Insull’s company obtained an exclusive franchise from the City of Chicago, acquired their competitor, Commonwealth Electric Light & Power, and largely extinguished any competition in the region. Insull had created a true electric monopoly.

Insull’s economies of scale pick up steam

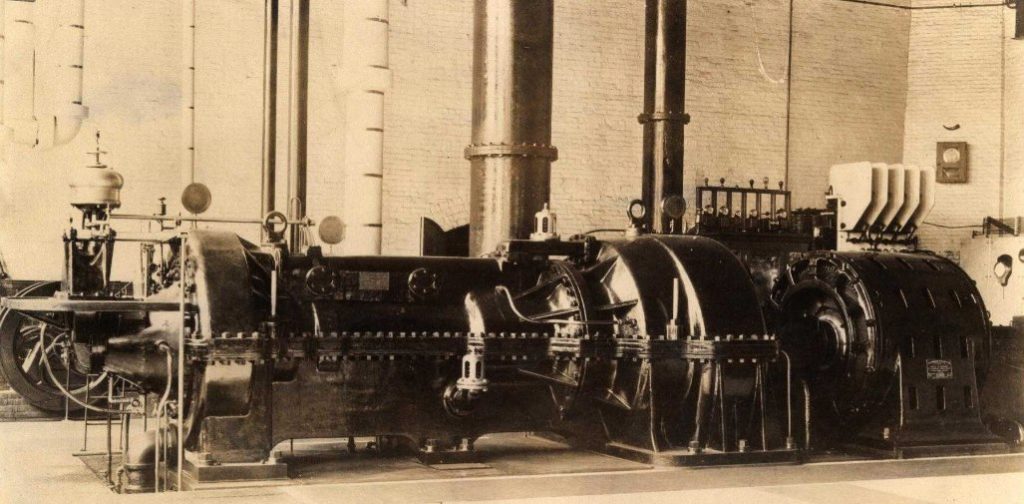

Insull understood the disruptive power of new technology. His success with AC grids emboldened him to be one of the early adopters of steam turbines in the early 1900s. Steam turbines dwarfed traditional power plants and could produce electricity at higher volumes and for less money than any technology before them. When running on AC power, these turbines could electrify entire communities from a single plant.

Insull’s company, now known as Commonwealth Edison, was expanding rapidly. He was buying up utilities and infrastructure inside and outside Chicago. With his financial momentum, his AC power grid, and his mammoth steam turbines, Insull was offering the lowest-cost electricity and sweeping up customers across Northern Illinois. He was achieving so much scale, he could literally shut down the power plants of his acquired competitors and repurpose them as substations connected to his AC grids and steam turbines.

The result of Insull’s audacious strategy was a monopoly that blocked out competitors and provided electricity at cheaper rates than ever before. By 1907, Commonwealth Edison had acquired 20 businesses. This strategy was soon emulated by competitors and, by the late 1920s, 10 holding companies controlled 75 percent of the American electricity industry. At one point, Insull’s electric empire controlled utilities in 5,000 towns across 32 states.

The making of the (Regulated) Monopoly Man

In the early 1900s, monopolies faced growing discontent from politicians and the public. Financial abuses from railroad monopolies further fueled concerns. The public saw these early monopolies as proof that the absence of competition led to higher prices and reduced innovation.

Many cities, towns and other municipalities responded by taking over the private electric companies and becoming their own utilities. They believed their lack of profit motives allowed them to serve customers’ needs better than shareholder-owned companies.

Facing the prospect of this growing trend ultimately leading to a government-run power industry, Insull began promoting the most audacious idea of his career: the regulated monopoly. He argued that municipalities lacked the technical expertise and business acumen to effectively run these complex utilities. For the private sector, he argued that competing power companies would inevitably build their own power lines and power plants. He said these overlapping investments were unnecessary and only led to higher prices for customers. His central argument was that electricity infrastructure was a “natural monopoly.”

Insull’s idea was hotly debated but eventually prevailed. Over the last century, the regulated monopoly has become the primary business model for electricity across America and virtually every other country in the world.

Holding companies or a house of cards?

Regulated monopolies freed Insull from competition. He could access more capital and continue to build economies of scale. But he was far from done. To keep expanding, he needed even more capital. Insull embraced a growing idea called holding companies. These organizations allowed a set of related businesses to be financially managed under a single legal umbrella. Costs could be consolidated via shared services. More capital could be raised at a lower cost. In fact, with only $27 million in equity, Insull built an empire worth more than $300 million (in current dollars, this would be a $300 million investment controlling a $6 billion empire).

The problem was that holding companies were also financially opaque. Investors rarely understood their inner workings. Regulators’ authority was limited to the part of holding companies operating in their state. Holding companies allowed a handful of companies to achieve enormous scale but the lack of transparency invited growing abuses.

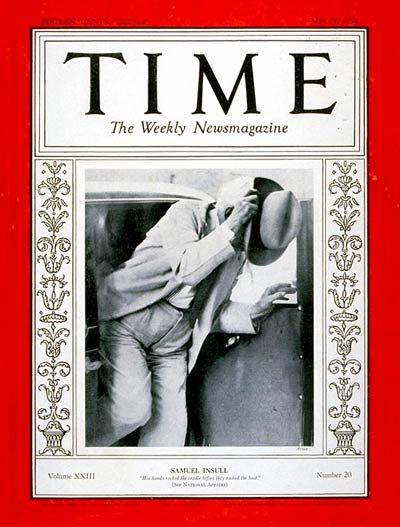

Soon, Insull’s holding company strategies were being widely copied. Great wealth was created. The stock market took off. But much of it wouldn’t last. As the Great Depression bore down on America, many holding companies, including all of Insull’s vast empire, proved to be a house of cards. His companies collapsed and took with them the life savings of nearly 600,000 of his investors.

For many of the public, Insull epitomized the greed and excesses that led to the Great Depression. Candidate for President, Franklin D. Roosevelt targeted “the Ishmaels and the Insulls, whose hand is against everyman’s,” as part of his promise to reign in powerful corporations. Charges were filed against Insull. He fled the country, first to Paris then to Greece, to escape the U.S. justice system. He remained on the run for several years. When he finally returned home in 1934, his trial proceeded. To the surprise of many, he was vidicated. He was found not guilty on all charges.

Electrifying every home in America

The Great Depression devastated the entire country, but rural America may have been hit hardest of all. Most farmers and rural families had never been connected to a grid. Homes were too far apart for utilities to profitably reach them with power lines. As part of his New Deal legislation, President Roosevelt believed that reviving rural America was key to reviving the country. He helped pass the Rural Electrification Act of 1935 which provided federal loans and expertise to electrify homes across every part of the country.

Samuel Insull’s risk-taking and commitment to new technology helped fast-track the power industry during its earliest days. While history may see him as both a hero and a villain, there is little doubt his innovations ultimately made electricity affordable to virtually everyone in America.

The era of Edison, Tesla, Westinghouse and Insull was a time of incredible innovation. Unfortunately, much of that spirit has waned. The structure and business model of the modern power industry is remarkably unchanged from that golden era. The industry has become deeply risk averse, falling back for too long on its comfortable position as a natural monopoly.

It’s time for the industry to try new business models, to allow for thoughtfully defined competitive markets, and to embrace new technologies. As Jim Rogers, the retired CEO of Duke Energy told me, “it’s time for electricity to be a technology business again.”

4 Responses

In amplification of the final thought in this article: The huge grids that span a third of the country at a time, are fragile, even indefensible. A single act of sabotage, either physical or cyber, can take months to repair. Local generation is needed for safety of electric availability, as well as being the best way to decrease the carbon footprint of energy generation.

I m probably the last person alive who knew Sam insull jr. Spent many hours with him while he had his daily two martinis. Much about him and he father has been misstated or totally wrong. (When he built the Civic Opera house, insull’s throne, yes the back of the throne faced east but it wasn’t that he was turning his back on Chicago, but to jp Morgan and new york) He has been greatly overlooked by the Chicago Historical Society, and the family plot in Graceland Cemetery bordering the pond there is ignored by the guided saturday tours of the cemetery.

Thank you for sharing. That’s a great perspective on a family who gets far too little attention from history.