(starting from Page 131 of Chapter 5)

One of the most thrilling and memorable events in my research for this book was my dinner with Jim Rogers. Jim, the retired CEO of electric utility giant, Duke Energy, is a legend in the power industry, in no small part because he was one of the first big utility CEOs to support the transition to renewable energy. Sadly, Jim passed away in 2018. But I remain grateful for the two hours he spent with me, sharing his story and giving me advice about my new career. It changed the course of my life.

Jim was a student of electric history. His stories of Edison, Tesla, and Westinghouse brought the early industry to life for me and inspired several sections in this book. Jim had recently published his own book, Lighting the World, about the tremendous opportunities for electrification among the low-income communities in Africa and India. It is a wonderful book that helped me focus my own passion in this area.

The dinner was long, and Jim gifted me with many great insights. The most powerful was this: “It is time for the power industry to become a technology business again.” As a refugee from the tech world, this was music to my ears.

His words were prescient. The power industry is slowly (very slowly) shedding its roots as a fuel-driven, asset heavy, top-down business into something increasingly defined by the economics of technology. This will require from the industry a completely different understanding of economics, because things like solar panels, batteries, electric vehicles, and power electronics all operate on a different business model than fuel extraction, large power plant construction projects, and transmission power lines. The economics of technology are unfamiliar to veterans of the industry, as is the driving force behind technology revolutions—innovation.

The dictionary defines innovation as “The creation of a new device or process that is contrary to established mechanisms.” When businesspeople talk about innovation today, they can sound like medieval philosophers talking about alchemy. “Innovation is the secret to creating better products, happier customers, faster growth, and higher profits.”

Every electric utility has a section on their website about their innovation. The term has become so popular that its real meaning has been lost. In too many cases, the term innovation is little more than marketing speak—a shiny veneer for an otherwise tired product or project.

But unlike alchemy, innovation is real, and in many businesses, it is alive and thriving, particularly in smaller, fast-growing companies. Under the right conditions, innovation can even transform long-established industries. We are seeing this today with the century-old electricity business, which, despite being one of the largest industries on earth, is experiencing a rebirth built around innovative thinking, driven largely by people from outside the industry.

Cutting-edge technologies, new business models, and tens of thousands of innovators are in the vanguard of this epic transformation. The coming changes will shake up electric monopolies and unleash incredible business opportunities.

I have seen this happen up close before. Several companies I helped lead earlier in my career—in computer networking, the internet, and digital marketing—were part of similar innovation-driven transformations. When I made the leap into clean energy, I devoted myself to learning how my previous experiences with innovation might apply to this industry. I wanted to separate out what critics call innovation theater (marketing veneer) from the elusive but very real opportunities for investors and startups.

This chapter and the next are about the underlying patterns of innovation, based upon my experience in other tech-driven industries. With these insights as a foundation, I will forecast the path of the renewable, local energy industry. Whether you are an entrepreneur, policymaker, venture capitalist, legislator, environmentalist, or a concerned citizen, I hope this helps you understand the treacherous divide between wild-goose chases and billion-dollar opportunities.

When I first began thinking about the business of clean energy, I reflected on my experience working as a venture capitalist at a firm called Greylock. In my time there, I met hundreds of entrepreneurs and reviewed thousands of business plans. This gave me an inside view into many of the successful companies the firm had funded. While there were certainly exceptions, I saw three common characteristics that created our biggest returns.

High gross margins. The money left over after the cost of making or selling something is called gross profit. When measured as a percentage of revenue, it is called gross margin. To illustrate investor economics, I will pick on the humble tomato. If a store buys each one for 80 cents and can sell it for $1, that leaves a 20-cent gross profit or a 20% gross margin. For tech investors, higher gross margins are almost always better. Software companies often exceed 90% gross margins, making them the darling of VC firms.

Asset light. Selling tomatoes is not asset light. You need cash to buy them or grow them. You must pay to refrigerate them and, inevitably, you will be stuck with some that do not get sold. In contrast, the digital products of asset light businesses—like music, video games, movies, TV shows, and software—can be duplicated for each customer at virtually no cost, avoiding the overhead of maintaining inventory. This not only lowers costs, but also allows a business to be more flexible and responsive.

Fast growth and disruptive market opportunities. Faster growing companies generate higher returns for investors. Growth allows companies to respond quickly to changing market conditions and to stay one step ahead of competitors. Venture capitalists are not investing in tomato companies because people eat largely the same amount year over year. Tomatoes have no “growth story,” as VCs would say. In contrast, software that displaces an existing market and grows rapidly—like Lyft and other ride-share services—disrupts existing industries with something faster, cheaper, and more convenient.

If software epitomizes fast growth and asset-light business models, the cleantech industry described in the MIT article is the opposite. For example, commercializing a new kind of solar cell is more than just breakthrough science. It requires enormous factories and complex supply chains, both of which consume a lot of cash. This kind of innovation is slow. The journey from lab-bench prototype to full-scale factory can take 3 to 5 years, sometimes much longer. Large customers, like utilities, can take years evaluating a new type of solar cell before they purchase it in volume. And once those solar cells are installed, they cannot be cost-effectively changed or upgraded for decades. No wonder the VC industry ran away from cleantech in 2011. Can the electricity business, or at least parts of it, ever become fast and innovative? The answer is yes.

Like all industries, cleantech is a synthesis of interlinked organizations, technologies, products, professionals, and business models. The journey from raw materials to manufacturing to distribution to customer benefit is complex. Business consultants refer to this as a value chain.

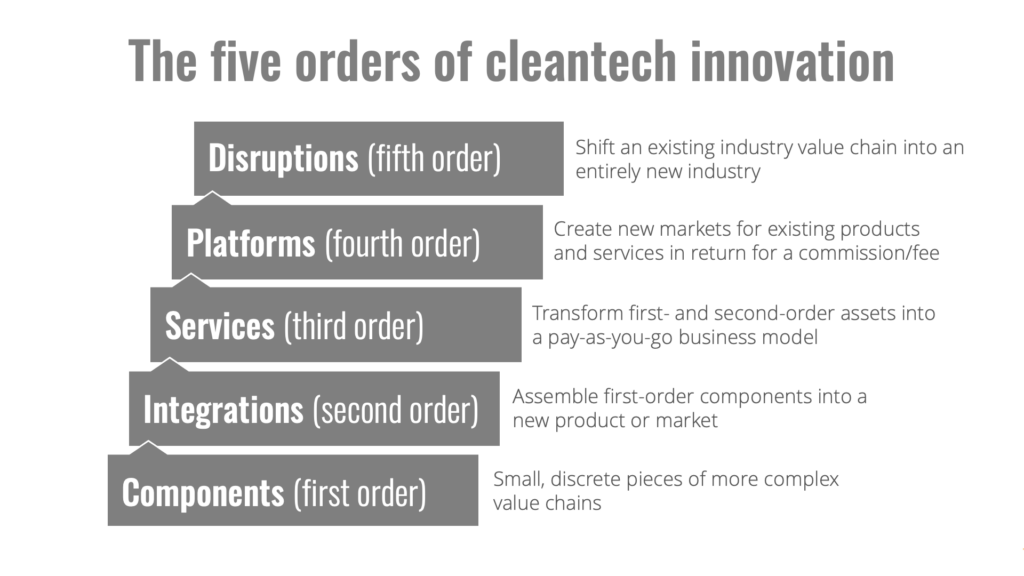

I like to think of each big link in the clean energy chain as orders, where each order is dependent on the one before it. The first order is components, the second is integrations, with services and platforms making up the third and fourth orders. The fifth order, disruptions, is the most exciting of all. For example, in the transportation value chain, tires, steel, and electronics are first-order components that feed the second-order market of automobiles. The third-order market transforms assets into services, like taxis and rental cars. Lyft and other ride services that leverage existing assets are fourth-order markets.

While exceptions are common, each of these orders tends toward its own unique set of opportunities, challenges, business models, and financing options. Understanding where a new technology or company fits into these orders simplifies the assessment of its risks and growth opportunities. In the rest of this chapter and the next, we will step through each of the five orders, explaining what they are and offering examples of each.

If you would like to read more, you can purchase Freeing Energy: How Innovators Are Using Local-scale Solar and Batteries to Disrupt the Global Energy Industry from the Outside In at Amazon or anywhere else books are sold in paperback, hardcover, Kindle, eBook, and audio book formats.

© 2021 All rights reserved