This is the first in our series on financing the clean energy disruption/revolution. Over the next few articles, we will cover the challenges facing the second chapter of cleantech investing as well as some of the emerging trends that have the potential for far greater returns going forward.

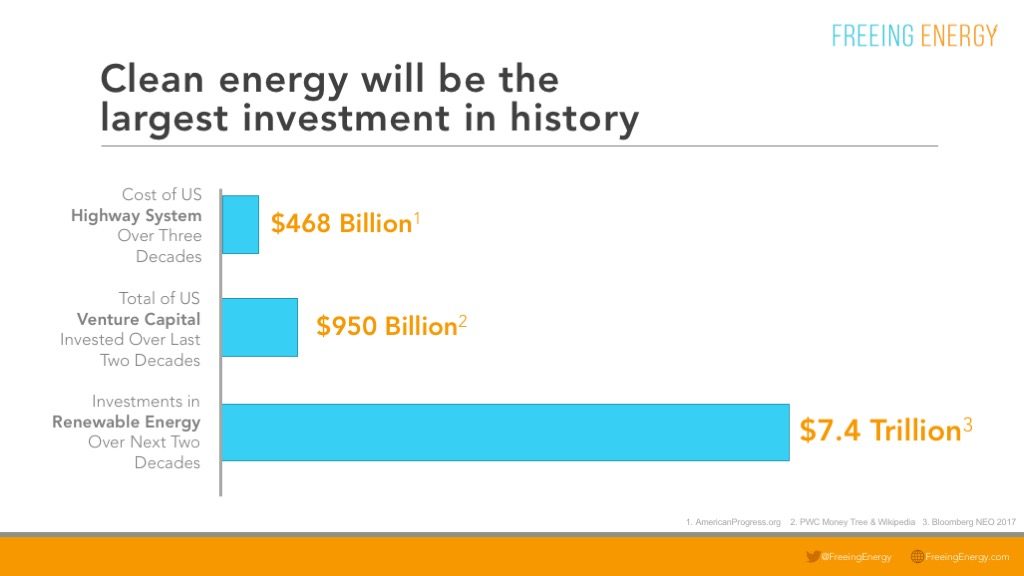

Clean energy is one of the largest business opportunities in history (see my article, The Biggest Business Opportunity in History). Even modest estimates predict investments of more than $7 trillion (that’s “trillion”, not “billion”) in the coming 25 years. By comparison, the internet revolution was funded with less than $1 trillion in venture investments over the last 25 years. In fact, what some call the largest infrastructure project in history, the US highway system, required less than half-a-trillion in inflation-adjusted dollars.

So, while researching my book, I was surprised to learn that funding for clean energy technology hit a very rocky spot a few years ago and has struggled to regain traction since. In fact, cleantech is practically a four-letter-word among some venture investors. What’s going on?

The epic rise and spectacular fall of Cleantech 1.0

In 2006, cleantech investing was white hot. Prices of oil and natural gas were on the rise and predicted to continue increasing. Public concern over greenhouse gas emissions was growing. Almost overnight, hundreds of venture capital firms rushed to fund technologies ranging from biofuels to improved solar power to energy efficiency. Billions were being invested. But then, as quickly as it sprung up, it all fell apart. According to the Brookings Institute, the percentage of money venture investors allocated to cleantech plummeted from 16.8 percent in 2011 to 7.6 percent in 2016. An MIT study says US venture capital firms lost over $10 billion on cleantech investments leading up to 2011.

Dean Sciorillo, of pioneering energy tech venture firm Enertech, describes it like this, “20 years ago, there were maybe 20 firms I could co-invest with that were doing energy tech deals. In the mid-2000s, there were almost 200. Today, the number is a fraction of that.”

Many armchair critics lay the blame on the VCs themselves, saying overconfidence led them to believe cleantech would be just like software. But this perspective ignores three much larger drivers of the Cleantech 1.0 collapse.

GET MONTHLY NEWS & ANALYSIS

Unsubscribe anytime. We will never sell your email or spam you.

The 2008 financial meltdown

White hot markets drove valuations sky high. The 2008 financial crisis brought everything crashing back to earth. Even potentially successful cleantech companies were left unfundable because valuations were too high. Skeptical new investors pressed for lower valuations. Existing investors negotiated vigorously to protect their early stakes. Along the way, companies ran out of money.

The fracking revolution

It turns out that the economics of energy was upended but it wasn’t from solar, wind, or biofuels. It was from horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, otherwise known as “fracking”. The price of natural gas had been predicted to continue climbing. But Instead, from 2006 to 2011, it plummeted from about $10 to around $3. Nathan Myhrvold, the one-time CTO of Microsoft and now co-investor with Bill Gates on nuclear startup, TerraPower, told me, “the hardscrabble fracking people did what all of Silicon Valley failed to do – they completely disrupted the energy industry.”

Natural gas emits less pollution and half the CO2 of coal. It wasn’t the perfect environmental solution but compared to the bogeyman of coal, it was cheaper, cleaner, and an easy plug-in replacement. Suddenly, the huge interest in zero-emission clean energy like solar and wind got put on the back burner (pun intended).

Silicon solar cells plummeted in price

No one saw it coming. From 2006 to 2012, the cost of silicon solar products fell a jaw-dropping 85%. This was due to a combination of scientific breakthroughs, loosening supply constraints, and huge investments from China and other Asian governments. It didn’t hurt that silicon solar cell manufacturing had a lot in common with computer microchips so there was already a base of expertise and equipment.

Regardless of the reasons, the price declines in silicon solar left competing solar technologies unable to keep up. Thin film solar companies, like Solyndra, and concentrating solar plants, like the Ivanpah plant, made impressive progress but they were ultimately too late. The juggernaut of silicon solar price declines had already left them behind. Other, more novel energy technologies never stood a chance.

Looking back, there were numerous technologies battling it out for low-cost leadership. Many were based on some kind of solar but other new energy sources like next-generation nuclear, biofuels, novel wind turbines, and fuel cells were also being funded and researched.

Danny Kennedy, the Managing Director or CalCEF, the state of California’s clean energy fund, told me that, “at the turn of the century, we didn’t know which energy tech would win. Now that argument is largely done.” Over time, silicon solar and wind power proved to be the least expensive for most situations. Fortunately, energy needs vary from location to location so the world will continue to require a wide variety of options. There will most certainly be applications for many of the other energy technologies, even if they don’t become the primary way we power the grid.

Cleantech 2.0 is already underway but how far can it go?

The lessons from Cleantech 1.0 provide a cautionary tale as we enter a new phase of clean energy investing. In the next few articles, I’ll be reviewing the traditional venture capital investment model and analyzing how it applies to different segments in cleantech. In the final article, I will be examining the resurgence of cleantech investing and what, in particular, has kickstarted Cleantech 2.0. I will explain why this second chapter has the potential to be far larger and far more successful, but, even more exciting, how it will likely be one of the largest investment opportunities of any kind in history.

One Response