This is the fourth article in our series on venture capital and clean technology. The first part explores the cleantech bubble of 2011. The second part asks, How are we going to fund the clean energy future? The third part lays out A blueprint for cleantech investing.

After years of spectacular growth, the cleantech industry collapsed In 2011. Investors went running for the hills and the industry was left on life support. Fortunately, there are once again signs of life. Cleantech startups are starting to show exciting progress and investors are slowly dusting off their checkbooks. As an energytech writer, an occasional angel investor, and a recovering venture capitalist, I get a lot of opportunities to help investors analyze funding opportunities. I like to start with these four questions:

- Does the investor understand the segment (or have access to a committed expert)?

- Where does the product/solution fall on the value chain?

- Who is the target buyer?

- How capable is the team?

Let me explain each of these.

Segment – hot or not?

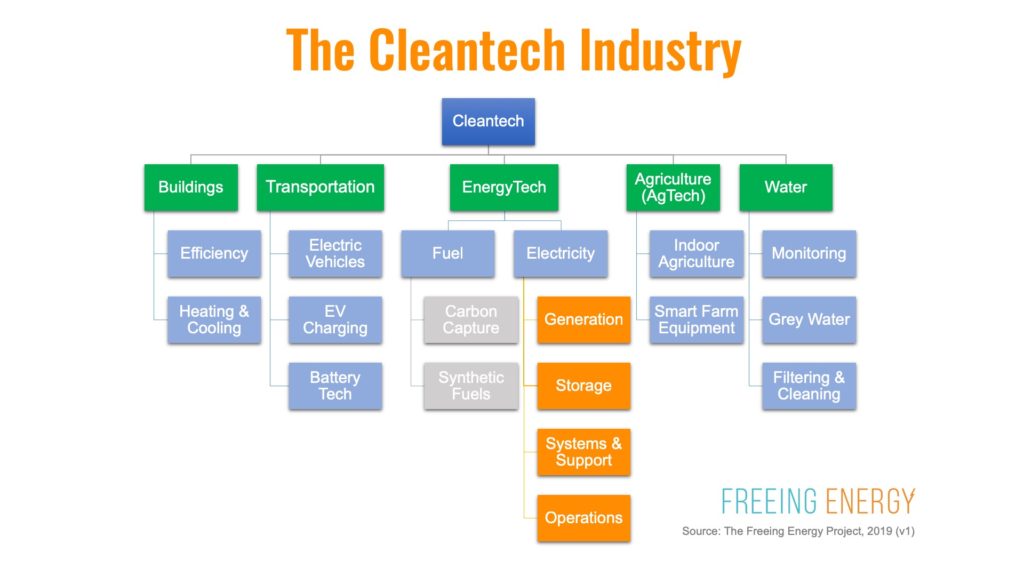

In my previous article, A blueprint for cleantech investing, I broke cleantech into five segments: AgTech, buildings, energytech, transportation, and water. These are vastly different businesses, each with unique regulatory environments, market dynamics, and competitive landscapes. All of these segments are filled with investing opportunities but energytech and its subsegment, powertech, are the most active right now.

Most cleantech segments are actually five-step value chains

To get a solution into the hands of the final customer, most industries are built on a sequence of processes and products called a value chain. This is like a set of stairs – each step is built on the previous one. For instance, a power generation solution like wind begins with specialized motors and turbine technologies. These get assembled in a factory. Software is added to coordinate and optimize the flow of electricity. Finally, the turbines are delivered and built into giant farms that produce electricity for the grid. Each of these steps has a vastly different risk and return profile.

GET MONTHLY NEWS & ANALYSIS

Unsubscribe anytime. We will never sell your email or spam you.

While there are many ways to slice and dice a value chain, I think of it as the five below:

1- MATERIALS AND PROCESSES

Characteristics: long, unpredictable development cycles; patent licensing

Ideal source of funds: government research grants; university labs; government labs; specialty VCs

This is hard science. It’s about wrestling with physics, chemistry, and sometimes biology to create breakthrough products and processes. Examples include graphite battery anodes, organic solar cells, fuel cells, and low-cost power electronics. Even when these breakthrough products work in a lab, materials are notoriously hard (and expensive) to manufacture cost-effectively at commercial scales. Promising solutions get widespread attention in technology and business media. Some of the biggest failures in Cleantech 1.0 were in the materials and process fields.

Because the cleantech industry is young, materials get a great deal of attention. Breakthroughs are frequent and can easily upend existing segments. My inbox is full of articles about more efficient solar cells and cheaper batteries.

2- COMPONENTS

Characteristics: low margins; low differentiation; ongoing R&D; shorter product cycles

Ideal source of funds: specialty banks; government guaranteed loans; limited VC

This is as much about traditional manufacturing as it is new clean technology. It often builds on breakthrough materials and processes that are ready for commercialization. It usually involves building massive factories to trim costs on very thin margin products. The Chinese government has supported its domestic industries and has created globally competitive component manufacturers in solar, wind, power electronics and many other fields.

3- INTEGRATIONS

Characteristics: supply chain focused; high volume products; heavier marketing and sales

Ideal source of funds: traditional banks; private equity; VC; family offices; social impact funds; suppliers

While this is still about building factories, it’s more about innovative ways of putting existing things together. It’s about complete, ready-to-use products. Tesla’s electric vehicles are a great example because most of their parts come from third parties and only a few components had to be designed or built in house. Other product examples include off-grid solar home systems, residential batteries, and microgrid solutions.

4- INFRASTRUCTURE

Characteristics: low margins; long, predictable cycles; each project is unique

Ideal source of funds: traditional banks; specialized investment vehicles; investment banks; governments

This is about deploying energy systems into the real world, like solar and wind farms. Infrastructure requires massive levels of long term funding. Because it can take decades to pay off construction debt, infrastructure investors are patient but also reluctant to try unproven technology. Cleantech infrastructure has a lot more in common with real estate or highways than any kind of traditional technology. It’s about finding locations, navigating local regulations, (often) partnering with local unions, tapping specialized finance providers, etc. Long term returns and thin margins make infrastructure a poor fit for venture capital investors although this hasn’t stopped a few of them from trying.

Interestingly, several of the early solar materials and components companies, like First Solar and SunPower, have survived by becoming infrastructure developers using their own products. This was done more for survival than strategic advantage.

5- SYSTEMS and SOFTWARE

Characteristics: fast product cycles; minimal assets

Ideal source of funds: VC, corporate strategic investors

This is the part of energy tech that VCs like the best. Software investments include smart grid management, demand forecasting, battery management, microgrid controllers, peer-to-peer trading, as well as customer-facing systems like websites and billing. As energy systems become more complex, software will play an increasingly strategic role. It will become one the most important areas of competitive differentiation.

Target buyers and target acquirers

Traditional software and internet tech investors often stumble when they dabble in cleantech. Amory Lovins, the founder and Chief Scientist of the Rocky Mountain Institute explained the challenge to me over lunch at his office, “a lot of you IT [information technology] people lose your shirts in cleantech. Regulated industries are harder than most people realize.”

The electricity segment of cleantech, what I call “powertech”, is not only regulated, but much of it is a government-granted monopoly. Giant companies like Consolidated Edison and Southern Company face little or no competition. A lot of powertech startups have failed because investors and management teams mistakenly assumed these giant utilities were variations of other large corporate enterprises – like airlines, healthcare giants, steelmakers, or software firms. In fact, these corporate giants are more like governments – their decisions can take years and they often have surprising constraints on their flexibility. One successful powertech software CEO told me that even after he signed contracts with several utilities, he discovered it was really just a “hunting license” – each power plant had its own decision makers and each took another year or more to close.

Fortunately, utilities can still be great customers if companies and investors understand the unique challenges. Even better, the power industry has two other major customer types: commercial and residential. Neither of these is a monopoly so regulations are much lighter. SolarCity made its investors a great return by focusing on residential customers. Countless startups are going after the commercial segment, which will likely be the most investable target customer of all.

The most important criteria for cleantech investing

Twenty years ago, I had the privilege of working for a venture capital firm called Greylock. On my first day, my boss Henry McCance, gave me a tour of their office. The hallways were lined with more than 100 framed IPO registration documents – a reflection of the firm’s unparalleled investing success. As we neared the last frame, he paused and asked me, “how many of these companies do you think went public on the business plan we originally funded?” Clearly, this was a trick question. I answered, “very few?” Henry said, “actually, not a single one.” He explained, “Markets and technologies are unpredictable. At Greylock we focus on the one part of a company that can weather the changes – we invest in management teams.”

My time at Greylock and my years since as an occasional angel investor have cemented Henry’s advice from that morning: The MOST IMPORTANT investing criteria is a capable management team. While investors prefer funding executives with lots of prior experience in energy and startups, this is a rarity in early-stage cleantech. Fortunately, deep experience is helpful but not a requirement. A passion for saving the world is important but, by itself, it’s not enough to grow a business. The most important skills in any startup team are collaboration, tenacity, intelligence, and a healthy dose of realism.

The Freeing Energy Perspective

How does all this come together? One particularly powerful example is the new $1 billion fund that Bill Gates has created specifically to fund energytech: Breakthrough Energy Ventures. The fund is focused on six areas that, together, aim to “commercialize energy innovation at scale”:

- “Incredibly cheap grid-scale storage”

- solar fuels

- global microgrids

- Zero-carbon building materials

- Geothermal

The largest challenge slowing the growth of the energytech industry is not technology, not regulations and not even a lack of funding… Across all of cleantech and powertech investors I have met this last year, all of them say the same thing. They all see plenty of interesting ideas but there are not enough qualified executive teams to transform the ideas into successful businesses.

One of my personal missions is to attract more seasoned startup executives into the clean energy industry. It’s unfamiliar and even uncomfortable for many of them but so was the internet back in the 1990’s. If you’re reading this and have grown a few companies and created great returns for your investors in other industries, please take a look at a recent presentation I gave: Help wanted – the clean energy industry could really use the skills of tech executives.