(this is the second article in a series on electric vehicles and the grid, click here to read the first article)

When Apple shipped the first iPhone in 2007, few industries outside telecom and tech took notice. But a few short years later, armed with cellular internet and built-in GPS, mobile phones became the unlikely weapon in a completely unrelated business – the vehicle-for-hire industry. In a single decade, mobiles apps from Uber and Lyft dethroned the taxi business, reducing it to a feeble market position of less than 10%. The battle between taxis and ride-hailing companies wasn’t just technical, it spilled into the courthouses and legislatures across the world. And, in the end, it was a strong preference by consumers for a cheaper, better solution that allowed Uber and Lyft to emerge as the dominant providers of vehicles-for-hire. As Clayton Christensen describes in his book, Innovators Dilemma (my favorite business book), disruptions come from surprising places, often far outside the industry affected.

So it is with the electricity industry. Like the taxi business, electric monopolies are heavily regulated and have enjoyed a century of little to no competition. Also similar to taxis, utilities are facing a fundamental disruption from a technology born far outside their sphere, electric vehicles. With all the focus on how EVs will help the grid, it’s important to look a few years further into the future and analyze how they will also be disruptors.

Talking about electric vehicles and the grid

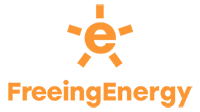

I recently had the privilege of leading a panel on the ways electric vehicles will transform the grid, as part of an event hosted by the Center for Distributed Energy at Georgia Tech. My previous article discussed how EVs will re-ignite a decade of stagnant growth in the electricity industry, and how they can help alleviate grid congestion and even use their batteries to provide power back to the grid. But all this opportunity and innovation occurs in a place entirely unfamiliar to electric monopolies: unregulated, competitive marketplaces. As opposed to the first article, this one takes a different perspective and explores three ways the rapidly evolving, technology-heavy EV business will disrupt and even reshape the century-old electric monopolies.

I recently had the privilege of leading a panel on the ways electric vehicles will transform the grid, as part of an event hosted by the Center for Distributed Energy at Georgia Tech. My previous article discussed how EVs will re-ignite a decade of stagnant growth in the electricity industry, and how they can help alleviate grid congestion and even use their batteries to provide power back to the grid. But all this opportunity and innovation occurs in a place entirely unfamiliar to electric monopolies: unregulated, competitive marketplaces. As opposed to the first article, this one takes a different perspective and explores three ways the rapidly evolving, technology-heavy EV business will disrupt and even reshape the century-old electric monopolies.

First, EVs will drag fierce new competitors into the electricity business

The shift from gas-mobiles to electric vehicles represents one of the largest threats to the oil business. When you consider that 71% of US oil is consumed for transportation, oil companies have no choice but chase their customers into the electricity industry or risk going out of business. But can they really compete? Yes, and then some. Oil companies have spent a century honing their skills in one of the most fiercely competitive markets on earth… and they are starting to turn their focus towards electricity. Their resources dwarf the electric utilities with the market caps of Exxon and Chevron alone exceeding the value of all the major US electric utilities put together. In a remarkable interview with the Financial Times in March of 2019, an executive from oil giant Shell described his company’s opportunity to become the largest electricity provider in the world:

“The amount of power [] we will need to be selling . . . will make us by far the biggest power company in the world. Many [electric utilities] are at a disadvantage, because they have this enormous legacy position, with coal plants and nuclear plants, but also a very centralised philosophy.” — Maarten Wetselaar, Shell’s director of gas and new energies.

He went on to describe the incumbent power companies as “useless” because they were shackled to outdated business models. In fact, Shell and other oil companies are already investing billions of dollars in EV charging and next-generation electricity solutions.

- Shell has acquired leading residential battery provider, Sonnen, digital energy platform, LimeJump, as well as EV charging providers, Greenlots and New Motion. It also acquired a UK power company called First Utility.

- French oil giant Total paid over US$1 billion for battery company Saft and already owns the majority of solar giant, SunPower. Total also acquired charging company, G2Mobility.

- BP acquired EV charging company Chargemaster for $170 million and invested in the ultra-fast-charge company, StoreDot

- Chevron is a large investor in leading EV Charging company, Chargepoint.

True to their ultra-competitive nature, the oil companies are playing both sides. Just as they invest in their own electric infrastructure, Politico reports that oil companies are spending heavily to lobby regulators against letting utilities make their own investments in EV charging.

But won’t the monopoly structure of the electricity industry protect the incumbent utilities? Not really. It turns out that EVs are the perfect trojan horse.

GET MONTHLY NEWS & ANALYSIS

Unsubscribe anytime. We will never sell your email or spam you.

Second, EVs open electricity monopolies to competition

For most of the last century, federal and state laws granted the right to sell electricity to a single monopoly provider per geographic region. But then electric vehicle charging came along. According to the North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center (NCCETC) Q2-2019 report on electric vehicle regulations, 32 states have exempted EV charging from utility monopolies. While EVs remain a small part of the automobile market today and the utilities provide the only source of electricity for chargers to resell (today), it is hard to overstate the magnitude of this change. As distributed energy generation and the electric vehicle markets continue their rapid growth, these seemingly small exemptions will be a foot in the door for the first real competition that electricity markets have seen since Thomas Edison’s competitors were stringing up their own DC power lines across Manhattan.

Third, EVs will spawn amazing new business models

As electricity sales move outside the rigidly regulated world of monopolies, new electric business models will begin to flourish. Here are a few of my favorites.

V2G – VEHICLE TO GRID

Charging doesn’t have to be one-way. Allowing EVs to discharge their batteries back onto the grid creates a surprising amount of value for utilities. Electricity from EV batteries can reduce the peak load required from the utilities’ power plants, avoiding expensive transmission and substation upgrades. Also, utilities can buy stored electricity from EV owners during peak load and avoid paying expensive wholesale electricity rates that often run $1.00 per kWh or more.

Here is a quick thought exercise to put the potential of V2G into perspective. For a state like Georgia, with 8.2 million cars and trucks, only one-third of those vehicles need to be V2G EVs to have enough collective battery storage to power the entire state overnight (and still have plenty of excess capacity for an average daily commute)1. This means with enough solar and wind power, it would only take a few million V2G EVs for a state like Georgia to run on clean energy 24-hours a day.

V2H – VEHICLE TO HOME

Mobile phones revolutionized the telecom industry by leapfrogging landlines. Electric vehicles can provide a similarly disruptive role and create a “mobile grid” by reversing the flow of electricity from the EV into the house or building battery. This may seem far fetched but it’s simpler and more feasible than it sounds. On cloudy days when your solar panels need some help, you’ll charge your car at your office or grocery store just a little more than usual and dump the extra power into your house battery when you get home. EVs like the Tesla Model 3 have enough storage to power the average American home for two days, and only a fraction of that capacity would be needed.

V2H isn’t limited to the cars you drive. New business models like “Uber for mobile charging” will emerge. Instead of picking you up for a trip, they’ll drive onto your two-way wireless EV charger and quick-charge your home battery. Expect Amazon and other delivery giants to embrace this as a way to sell more to each customer and increase their profits.

REUSING RETIRED EV BATTERIES

Current EV batteries are designed to last 8 years, at which point the batteries’ capacity and driving range have typically dropped 70-80%. Most car owners will replace the batteries to get back the longer range but the old batteries remain entirely functional. For example, when a low-end Nissan LEAF battery drops to 75% capacity, it can still store 30 kilowatt hours, which is twice the storage of a Tesla PowerWall 2 home battery. Since most cars will be paid off in 4-5 years, those used batteries are effectively free for the owner and can be put into the service of a home or building at astonishingly low costs.

The Freeing Energy perspective

For the next few years, electric vehicles offer exciting opportunities for utilities. Building out charging networks, reducing peak load grid congestion, and renewed growth in electricity sales will all benefit the grid and its owners. But as EV penetration increases, gasoline sales slowdown, and investors embrace new business models, the utilities will find themselves on the defensive. EVs will slowly chip away at the century-old electric monopoly business model and create the first real options for electric competition and innovation.

Many of our readers ask me what they can do personally to help accelerate the transition to clean energy. One of the easiest things you can do is purchase an electric car. As gas stations and engine maintenance fade into your past, you’ll wonder how you lived your life dependent on dinosaur juice. And, along the way, your EV will be part of a growing movement that is reinventing the electric industry from the inside out.

Additional reading

- Great overview of EV battery technology from UCS: Electric Vehicle Battery: Materials, Cost, Lifespan

- Cost – Batteries (bc).xlsx, Freeing Energy, tab bc.3 [↩]

4 Responses

Oil companies in Texas and North Dakota are flaring off large and increasing amounts of natural gas, methane. Until this gas is being sold instead of flared off, natural gas, at home, should be regarded as Green House Gas [GHG] free, because if it isn’t used, it will be flared off.

Charging your electric car at home, from a methane fuel cell, will lower your costs by at least 40%, and contribute zero to GHG emissions. Using solar, and using the fuel cell to decrease the size of the home battery, and still cover any intermittancies, will lower your costs even more.

This approach is truly in accordance with the freeing of energy from the monopolies.

Newt and Bill – Fascinating discussion. Is it possible to see the economic comparison of the 2 approaches. Perhaps both are valid depending on the proximity to the source of energy. If you are in Texas where the flaring occurs, this may make sense. I believe Enchanted Rock is using the flared off methane to power their stationary batteries.

Tracy and Newt – thanks a bunch for chiming in here!

As I understand it, flaring and venting occur most often as a side effect of a well drilled for oil. These wells aren’t connected to gas pipelines so there is no way to make use of the gas. The amount of wasted gas is enormous but apparenly it’s not valuable enough to connect the well to a pipeline.

Newt, your idea really reasonates. Do you have any thoughts on how to get all this excess gas into people’s homes? Is this something we should regulating or do you foresee more cost effective ways to compress onsite and deliver via trucks?

In terms of flaring vs ventig… since methane is 20-80 times more potent than CO2 in terms of atmospheric warming, flaring would seem to be the strongly preffered option, even if it does create a lot of CO2. I’ve also read that flaring/burning the gas destroys a bunch of toxic gases that can be mixed in with the methane.

There’s a great article on this here: https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/energy/flaring-or-why-so-much-gas-is-going-up-in-flames/2019/09/04/f3db2166-cf1b-11e9-a620-0a91656d7db6_story.html

I am guessing that if they have a well with so much natural gas they are flaring it, then if they could install a hydrogen reformer, and change that leftover gas into hydrogen, it could be transported to a location where it can be used. Also they could be running a diesel or natural gas generator on the “Flared” natural gas, and send that to the grid.

Long Beach California runs most of it’s 8.3L Cummins diesel engines on a mixture of 90% natural gas and 10% diesel fuel for trash collection and other vehicles. This has reduced their diesel fuel bill from over 2,000,000 gallons in 1995 to less than 200,000 gallons a year in 2010. The engines burn much cleaner on natural gas, don’t require as many oil changes per 100,000 miles, time between overhauls has greatly improved!

On the electric car subject, my Ford C-Max plug in hybrid has a 20 mile range with it’s 7.5 KW battery and gets 40 MPG with it’s 2L engine. So I can drive about 30 miles per $1 on electric, and 10 miles on gas at the current $4 per gallon.

I would recommend a Mach -E or electric Transit to anyone who is driving less than 120 miles per day! You will save at least $500 in fuel costs per year.