This is the first part in a series from my recent visit to Puerto Rico to understand how local, clean energy is remaking the island’s electric system. This first part is about resilience.

“Have you ever heard lots of wolves howling at the same time? The hurricane sounded like wolves howling.”

Celines Pacheco Lopez is an English teacher at the middle school in the rural municipality of Naranjito, located in the mountains of central Puerto Rico. She was telling me about the morning of September 20, 2017, when Hurricane Maria struck the island. “The wind was going all around our house, and then everything was still. The eye of the hurricane was passing by. Then everything started again but backwards.”

When the storm finally passed over, she went outside. Her cement house had managed to survive. But she began slowly shaking her head as she recalled what she saw, “My uncle’s house right next door was made of wood and it was completely destroyed. They lost everything. Some of their furniture landed in the river and some of it landed on the bridge.”

“We couldn’t get out because we were blocked off by a mudslide, so we had to dig. Everybody with a shovel started digging. And, when we got out, we found that another mudslide had taken out the main road and it had collapsed. It was like three to four days after the hurricane before we could finally get out.”

GET MONTHLY NEWS & ANALYSIS

Unsubscribe anytime. We will never sell your email or spam you.

Celines was the first teacher to reach the school. “When I got here I couldn’t open any of the gates because all the trees were blocking it. Electrical cables were everywhere. The roof of one of the businesses that’s over here, it ended up wrapped around my classroom. When we finally got the gates open, it was a disaster inside. Maria had ripped off the roof of my classroom.” I asked her how they cleaned up the school. “We’re all female staff. So we were dragging, you see like 10 teachers dragging a limb across the street, dragging pieces of metal and garbage everything.”

Everyone I talked with, from mountain communities to downtown San Juan, had the same story about the hours and days after Maria. People came out of their homes, they shook off the daze, and got to work. They checked on the elderly and other vulnerable neighbors. And then, without any instigation, they just banded together and started cleaning up. Celines told me that without the community, the school would have remained closed another month or two as they waited for officials to arrive. “Everyone pitched in.”

Puerto Rico teaches us just how dependent we are on electricity

The tragedies inflicted on Puerto Rico from Hurricane Maria lay bare our society’s utter dependence on electricity and the many ways–often imperceptible–it makes modern life possible. The blackout’s biggest impact was water. In a place like Puerto Rico, there is no water without electricity to power the pumps. Faucets ran dry and toilets wouldn’t flush. Beyond water, medications, and food quickly spoiled due to lack of refrigeration. Life-saving medical equipment went dark. One woman told me that her brother had been in a hospital on life-support when Maria hit. The hospital’s generators worked for a few days and then failed. Her brother passed away before they could be repaired. Gasoline stations couldn’t pump gas. 85% of cell phone towers remained off-line for weeks, largely due to lack of power. Elevators stopped working, leaving multi-story buildings inaccessible to anyone with physical limitations. Disease spread, emergency services became overloaded. As Puerto Rico became an island of generators, the already economically devastated communities were forced to pay for diesel fuel, one of the most expensive ways to generate electricity.

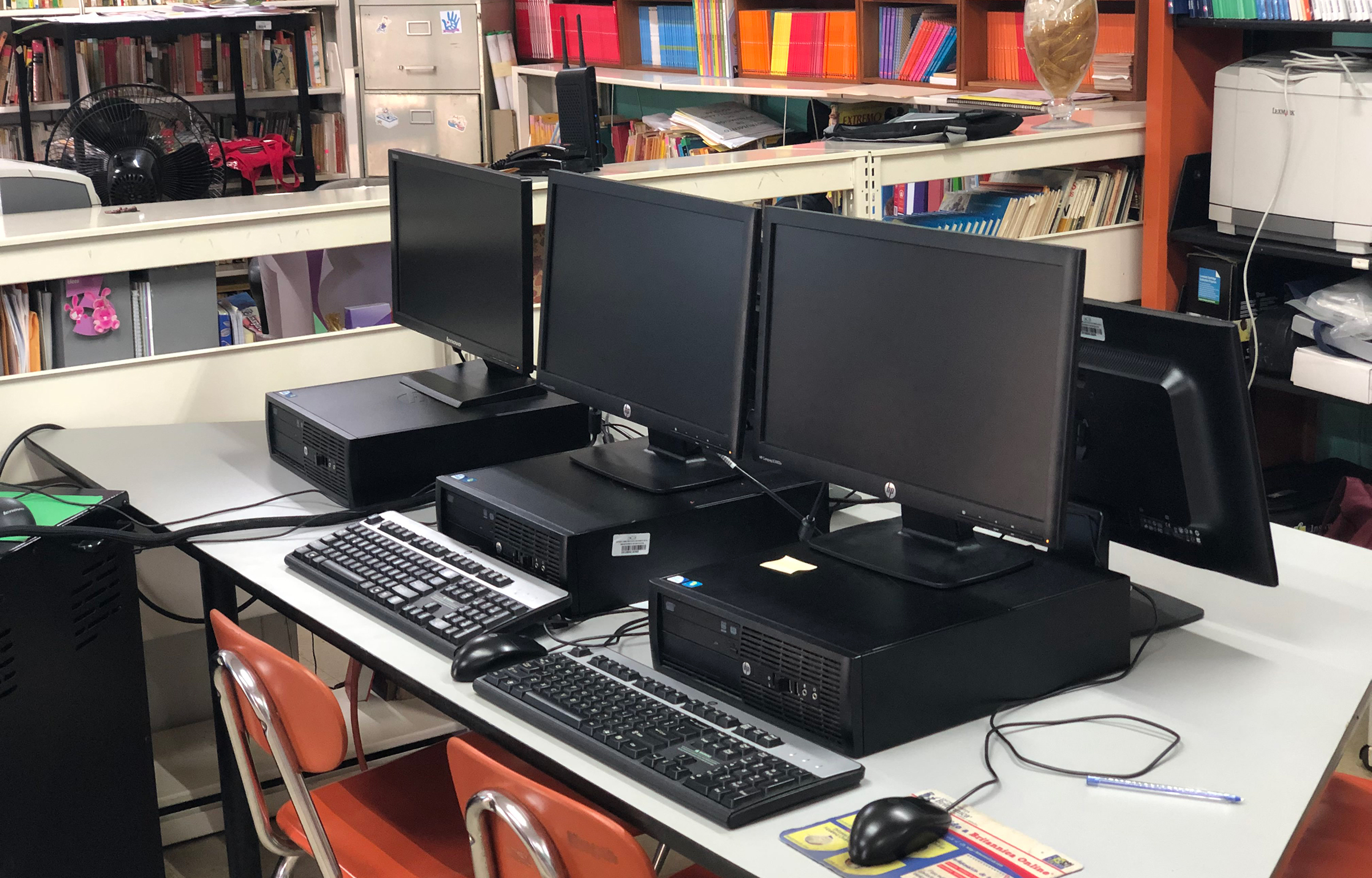

Back at Celines’ school, the lack of electricity kept the school closed for months. 300 children, kindergarten through eighth grade, had no place to go. Some had lost their homes and even lost people they loved. Others had friends who moved away, hoping to find a better future on the mainland. Parents were forced to stay at home, often missing work and even losing their jobs. The school’s closing wasn’t about lights or air-conditioning. It was about toilets. The school is built on hills and only one toilet could remove waste with gravity. When a generator finally arrived on the scene, it was put to use powering sewage pumps. But this was a start, and three months after Maria, children started passing through the front gate once again, each being asked to bring their own water because faucets remained dry. For the next few months, classes were limited to half-days because there was no refrigeration to store food for meals. Eventually, almost six months after Maria, the lights, and refrigerators, and computers flickered back to life. The middle school in Naranjito was one of the last schools to have grid power restored on the island.

The Freeing Energy Perspective

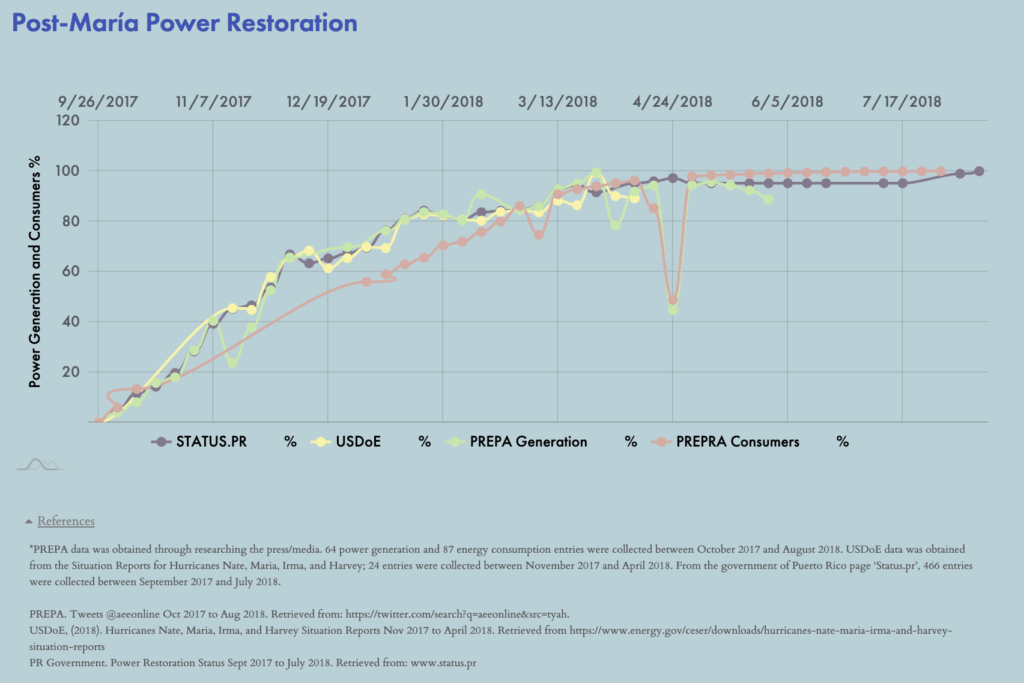

Puerto Rico’s power outage was the longest in US history. Fewer than one hundred people were killed by Hurricane Maria’s high winds and flooding. But the suffering caused by the prolonged blackout was on a scale never before seen in a prosperous, industrialized country like the modern United States. According to a George Washington University study, nearly three thousand more Americans died in the months that followed, almost entirely due to the lack of electricity. It took 2 months to restore half the island’s power and a stunning 11 months before PREPA claimed restoration was complete.

As I sat with Celines in her classroom two-years after Maria, she told me things are mostly back to normal. “But, we’re still having problems with the material that we weren’t able to cover.” It will take another year or two to catch up on all the lessons that were missed and probably much longer for life to start feeling normal again.

If you’d like to a part of these efforts and help bring resilient electricity to schools in Puerto Rico, click here to learn more and here to donate.

The second article in the series is here: Puerto Rico after Maria: From generator island to a solar microgrid revolution (part 2)

3 Responses

If the energy sources had been more diverse, before the storm, then restoration could have been on a more selective schedule, and the school would probably have been fully operational sooner. If the restoration had been done in microgrids first, then, finally, linked by a grid, the island would be much better off, when the next hurricane hits.

This was a great podcast. I think that the role of micrograms in the post-Maria recovery is something that needs much more exposure here on the mainland. Thank you, Bill, for shining a light on these important developments.

Very informative and educational about the process of re electrifying areas damaged by severe weather. I believe that we should do everything in our power to conduct ground breaking research into self sufficient power sources that just need the proper approach to tapping into this unlimited free power source that this amazing planet of ours emits on a daily basis we just need to pump some funding and education in research to achieve the most fonominale discovery of mankind since the days of Egypt’s height in power and long forgotten technologogy that was handed down from the Gods themselves. We just need to find a way to look at and solve the greatest mystery of our modern era. ” How to produce a self sustaining power source free to all humans. For the comfort and advancement of our kind… Lets change the world people one obscured idea at a time mixed with a dash of hope and faith that if our ancestors accomplished such an amazing feat. Why in today’s world with all the knowledge of man at our fingertips are we not capable of solving this world wide delema . We can do it people we just need to focus our collective minds on this issue and we will find the solution to this thousand year mystery. That and so much more i believe in the power of working together to solve issues we have together as one consciousness manifesting a cleaner healthier future for all the people and animals of this beautiful planet.