Puerto Rico has become an island of generators.

Almost 10 weeks after Hurricane Maria tore across the island, more than 40% of Puerto Rico still lacks access to grid electricity. Actually, this number is the power company’s (PREPA) self-reported electrical generation capacity. No one really knows the number of people still without power so it’s possibly much higher than 40%.

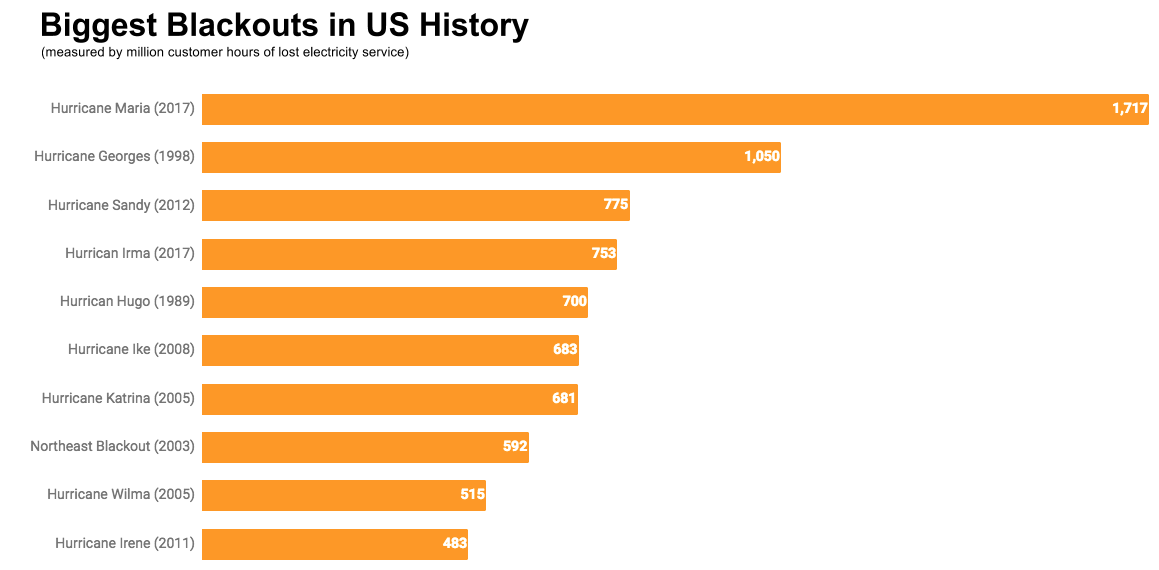

According to data from the Rhodium Group, Puerto Rico’s power outage is now the longest power outage in US history.

The island has become a compelling but tragic story about the central role electricity plays in modern lives. Even when the grid is offline, people will go to amazing lengths to get power. Generators have become lifelines even if they are a poor substitute for the real grid. Fuel is hard to find and high prices make the electricity extremely expensive. Most generators are underpowered and none were designed to run for the months they are enduring now. At best, people can power lights, chargers, TVs and maybe small refrigerators. Air-conditioning, water heaters, washing machines, electric stoves, microwaves, vacuum cleaners and other modern conveniences largely sit idle waiting for the grid to come online again.

GET MONTHLY NEWS & ANALYSIS

Unsubscribe anytime. We will never sell your email or spam you.

Why is Puerto Rico’s grid so hard to fix?

After Harvey and Irma, nearly everyone in Texas and Florida had grid electricity restored within days or weeks. Puerto Rico’s blackout has lasted months and a complete restoration is still months away. What makes it so different?

The perfect storm caused by a perfect storm

The devastation from Hurricane Maria was caused by a number of factors, all coming together at once. Not the least of which is the intensity of Hurricane Maria. It’s the most powerful storm to hit Puerto Rico since the San Ciprian Hurricane of 1932 (also a Category 4). And, back then, the population was less than half today’s 3.4 million.

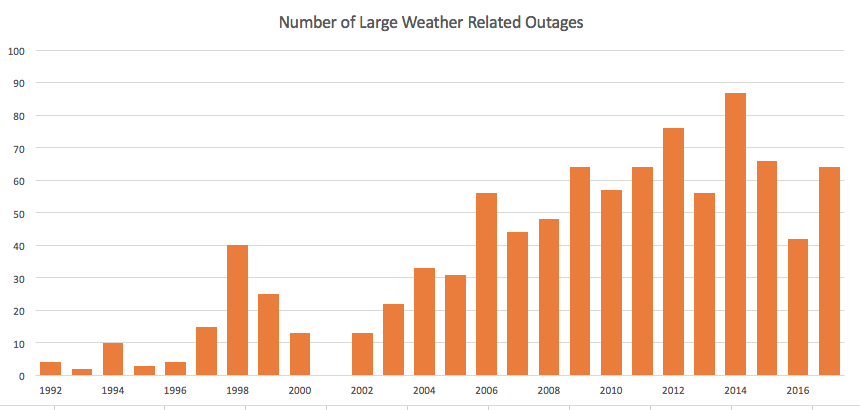

Before we get comfortable that storms like this are once a century, take a look at the graph below. Outages from extreme weather events are on the rise so trends suggest Puerto Rico may have far less than 80 years before a similar or stronger hurricane comes through again.

Supplies and workers must be brought in by boats

Puerto Rico is an island. After Hurricane Maria, shipping ports were damaged and quickly became choke points as emergency supplies flooded in. Vehicles and fuel were scarce. Even before they could get on boats and planes and head to the island, early responders and repair crews needed to know there would be food and shelter for them once they arrived.

Compare this to the mainland. When hurricanes were approaching Texas and later Florida, thousands of repair personnel were queued up just outside the storms’ reach. When the weather settled down, people just got in trucks and drove to areas needing repair. At the height, more than 5,600 workers from New Jersey, Oklahoma, California and elsewhere were working in South Texas. Full power was restored within two weeks.

Puerto Rico’s terrain is rugged

2,478 miles of high voltage power lines connect distant power plants to the population centers across the island. Many of these power lines traverse terrain so rugged they can only be reached by helicopter.

Puerto Rico’s power utility (PREPA) was bankrupt

In July of 2017, with nearly $9 billion in debt, PREPA declared bankruptcy. Years of losses, aging equipment and lack of maintenance had left the Puerto Rico grid in dire shape. In fact, in November of 2016, a power plant exploded which took out two transmission grids and left the entire island without power for three days.

With no credit, PREPA was unable to set up the kinds of mutual assistance agreements that most utilities have with each other. And when Hurricane Irma and then, two weeks later, Maria, destroyed the grid, the executives at PREPA struggled to convince any company to come to the island without pre-paying their contracts. Initially, only one company was willing to take the risk of working with a bankrupt utility: a tiny contracting firm out of Montana called Whitefish. Whitefish brought in equipment and hundreds of people but within a month, the contract with Whitefish was canceled as it spiraled into a political rat’s nest. Whitefish packed up and returned to the mainland, adding countless additional weeks to the long process of full power restoration.

Very little clean, local energy

Despite having abundant sunlight and wind, PREPA had only recently begun to deploy renewable energy. Before Maria, some 47% of Puerto Rico’s electricity came from petroleum, 34% from natural gas, 17% from Coal and only 2% from renewable energy like solar and wind. Notably, most of the power plants survived the storm intact. It was the damage to the tens of thousands of miles of exposed, above-the-ground power lines that are largely responsible for the outages.

For the next few months, the island’s leaders are entirely focused on restoring the grid and returning electric power to everyone that had it before. FEMA is actually restricted from making any improvements to the infrastructure after a disaster – they are only allowed to restore it to the state before the disaster happened. For the time being, the repaired grid will look a lot like the pre-hurricane grid – just as vulnerable when the next major hurricane comes knocking.

In the next post, I will be looking at vocal and powerful debates on how the Puerto Rico grid should be rebuilding and I will share the lessons learned in New York five years after Superstorm Sandy left half a million people without electricity for a week.

Extra Reading

For a complete timeline of the hurricane and the race to restore power, click here.